09th Feb 2023

2018 is a vintage that took Bordeaux's vines and winemakers to the limits of what they could produce. Some legendary wines were made this year, a few that I firmly believe avid Bordeaux collectors will not want to miss.

Extreme

2018 was extreme at each critical stage of the growing season: extremely wet to begin, then extremely hot and dry. The wines are also extreme and, therefore, divisive. Some legendary wines were made this year, a few that I firmly believe avid Bordeaux collectors will not want to miss. However, the vintage was heterogenous in quality compared to other successful warm, dry years such as 2009, 2010, 2016, 2019, or 2020, in as much as modern viticulture and winemaking allow for vinous train wrecks these days. What continues to be apparent after a little more time in the bottle is that the best results all boil down to location. Another not insignificant factor is that this year's conditions resulted in extreme pressure on the vines that people sometimes required to produce their most outstanding achievements ever. But the real key to consumer buying decisions boils down to vintage style. This is an atypical vintage. Some Bordeaux lovers won't like these bigger, richer, higher alcohol, tannic (albeit ripe and plush in the best cases), and lower acid wines. Others won't be able to get enough.

Growing Season

2018 began with a deluge. There was an extremely long period of sustained rain from January until mid-July. This didn't impede the flowering and fruit set too much, except for a few growers that experienced coulure and therefore reduced yields (mainly impacting Merlot). Otherwise, a lot of vineyards were set for a good-sized crop.

As the late spring/early summer temperatures heated up, the soggy conditions called for fast-acting evasive maneuvers to avoid significant crop losses from downy mildew. Many organic and biodynamic vineyards took a big yield hit from the mildew, including top estates such as Pontet-Canet, Latour, and Palmer. Those that were right on top of their vines when the flare-ups occurred had a chance to save at least some of that section of the crop; others were not so lucky. Successfully managing the mildew depended on location, grower vigilance, and, in some cases, just plain luck.

Hail on May 26th and July 15th resulted in a few isolated cases of significant crop loss, especially in Sauternes (see below).

From mid-July, the rains dried-up, and extreme heat and dry conditions ensued through to harvest. "From mid-July, it became very dry and very hot," said Eric Kohler, Château Lafite's technical director. "This was the hottest summer since 2003. Of course, it was not as extreme as 2003. This is why the potential of the terroir was very important. What is a great terroir? It is a terroir that can compensate for the excesses of the vintage. The terroir must have the capacity to behave like a sponge—to retain or give water. The sponge of clay that we have at Lafite regulated the excesses of the vintage. This year instead of the humid wind from the west, we got a dry wind from the northeast. So, there was no risk of botrytis as harvest approached."

Dry white grapes began coming in from late August, offering ripe, exotic fruit styles with impressive flavor intensity but perhaps not the aging potential that cooler vintages with longer, slower ripening periods and fresher acidity deliver.

As for the red grape varieties, younger vines and those on particularly free-draining soil types (e.g., deep gravel and sandy soils) began to falter due to hydric stress come September in areas that saw little or no rain up until then. The lack of rain in September and October left red grape harvest windows wide open to winemakers' visions/interpretations of the vintage with varying degrees of success. Tiny berries with thick skins and a lot of tannins to ripen (not to mention generous crops for those that got through the mildew relatively unscathed) meant that red varieties required a good amount of hang time to fully ripen tannins. A number of later-harvested vines suffered from berry dehydration/shrivel, dropping yields some and resulting in stylistic changes, occasionally to the detriment of quality.

Red Winemaking

In virtually all of Bordeaux's cellars, extremely gentle extraction was this vintage's winemaking blueprint due to potentially high levels of tannins, which, in some cases, were not perfectly ripe.

"In 1986 and 2005, we were not afraid of extraction," said Philippe Bascaules, Managing Director of Chateau Margaux. "In 2005, we recognized the higher alcohol. It was 14% then too. In 2018, when we saw that the extraction was becoming too high, we knew what we had to do. The alcohol is a big solvent for tannins, so we had to adapt the winemaking—for the balance. In just 24 hours, you can have too much tannin; you can go too far. You must anticipate it before. We have to learn a little bit better with each block, with each lot. The day after can be too late. Fining doesn't choose the worst tannins. We analyzed the tannins twice per day. There were some tanks where we did not even do any pumping over! This was the first time for us. I think we will have this situation more and more. We have to change a little bit our strategy, but I would rather have it this way—to pull back—than not have enough. In the end, in 2018, we did have some wines that had too much tannin, so we did not put these into Margaux."

Apart from getting the tannins right, the other major winemaking factor that resulted in the greatest successes in 2018 was the blending decisions. In a warm, dry vintage climate or vintage, the best winemakers know that the challenge is not merely to express ripe fruit and generosity but to balance this with freshness and tannins that are firm enough to support the fruit but not so hard and astringent as to make the tasting experience unpleasant, at any stage. For a lot of technical winemakers and/or those that are new to a property, this is the goal. And it is a critical goal. Many good and even outstanding wines can be thus produced in very warm and dry regions and vintages. But, for those winemakers with a deeper understanding of their vines and site, these attributes are viewed merely as the starting point. The real challenge is restraining the vintage's signature just enough to let the site shine through to retain the vineyard's signature in the context of an extreme vintage. It can be the difference between a sculptor producing a well-crafted, anatomically correct likeness of a man and Michelangelo's David. The former gets the general point across and is suitably fit for purpose, but the latter takes your breath away.

The Tasting

In 2022, I participated in a three-day blind tasting of Bordeaux 2018 in London, hosted by Farr Vintners and organized thanks to the invaluable help of Bill Blatch. This annual blind tasting of Bordeaux wines one year after their release has come to be known as the Southwold tasting.

Of course, I've rigorously tasted all these major 2018s before, in barrel and in bottle. Retasting over 200 of the top wines of this vintage at Southwold, the striking common feature of the most successful wines of the vintage is the brightness of fruit and quality of tannins. It is like tasting another vintage compared to those wines that merely ranged from average to very good. Why? The main factor the successes all had in common was core vineyard areas that had availability to water in the soil profiles, generally meaning the presence of clay or limestone. Another critical factor was vine age—older vines with deeper root systems and thicker cordons with more stored carbohydrates consistently demonstrate the ability to withstand periods of extreme heat and drought better than younger vines. This means older vines tend not to shut down or become sluggish. The third major factor in success in 2018 was ruthless selection—using only perfectly ripe fruit that was neither underripe nor raisined. Finally, the aforementioned winemaking decisions played a critical role in relative success.

Red Styles & Quality

The styles of some 2018s are extreme. There are some big tannins (albeit at best, cashmere-soft), alcohols on the high side (generally 14.5%), low acids/high pHs (pHs in the 3.8-4.0 range are common), a lot of fruit, a lot of power and a lot of density. At the very peak of quality, the 2018s are incredible. In this upper realm, terroir signatures marry with the character of this vintage to produce wines that speak of both place and time.

Alcohol and body are two of the most significant factors impacting style preferences of dry red wines. All the wines in our Wine Independent database have expertly judged body descriptions, and most reveal the stated or actual alcohol levels. Readers can filter wines by body and alcohol level on our site, and I urge you to take advantage of this. In 2018, there are many wines with alcohol levels above 15%, especially from the right bank. There are also wines with alcohols as low as 13.5%.

The top 2018s will have broad drinking windows. In some cases, rich, already flamboyant fruit and beautifully plush tannins mean they are approachable at a relatively early stage. Others will need more time to come around. The top 2018s will also be very long-lived, easily cellaring for 40-50 years and sometimes many more. As always, each review in this report comes with an anticipated drinking window, some of which have been adjusted considering this recent tasting.

2018 is not as qualitatively consistent as 2009, 2010, 2016, 2019, or 2020. This vintage has also produced a good-sized lake of less successful to mediocre wines, which can be disappointing for any of the following reasons: 1) Low acidity/high pHs rendering some wines a little "flabby," 2) "hot" finishes from higher alcohols, 3) Slightly chewy to downright hard tannins and/or 4) Simple fruit profiles mainly from early-harvest or baked fruit/late-harvest characters or lack of winemaker vision.

It must be said there are quite a few ordinary, hard, lean, and rustic wines at the lower end of the 2018s—many of which we didn't taste at Southwold. The disappointing wines are mainly a consequence of vine blockage and berry dehydration. At the other end of the spectrum, tasting these wines again, I found there remain some very exciting wines. I would even go so far as to say there are some absolute legends in the making.

Sauternes

Throughout late spring/early summer, Sauternes shared many of the same challenges as the rest of Bordeaux, notably in the crop losses due to downy mildew, but with the increased risk of hail. In this respect, 2018 was a similar story to what happened elsewhere in Bordeaux, but with particularly low yields for an already low-yielding region from the mildew/hail double whammy. Château Raymond-Lafon's comment of losing a third of their potential crop to mildew at the beginning of the growing season is not uncommon.

On July 15th, parts of Sauternes were pummeled by hail. Châteaux Guiraud and de Fargues especially took a beating, and Rieussec also received some hail damage.

From mid-July, the weather turned very warm and very dry. The reprieve from the mildew was welcome at first, but come mid-September, producers in Sauternes were getting nervous again. There was no botrytis.

"Part of the reason 2018 was so great for the red wine is we had such a long, dry, sunny period—which isn't what you want for botrytis," said Christian Seely on behalf of Suduiraut, both properties under the AXA Millésimes umbrella. "Botrytis arrived pretty late, making it a very late harvest indeed." At Suduiraut, yields were a lamentable five hectoliters per hectare this year.

A number of producers started to get itchy secateurs by the third week of September. In late September, many winemakers opted to make a first pass in the vineyards to bring in the "passerillage," or shriveled berries, that were unaffected by botrytis yet possessed sugar levels conducive to producing a late harvest style at the very least. An insurance policy barring complete disaster.

Finally, in early October, the weather cooled and turned sufficiently humid to encourage the slow onset of botrytis. A little rain during October 6-8 got the fungus progressing steadily before things kicked off in mid-October, following some much-needed rain on October 15th and 16th. Speaking on behalf of Rieussec, part of the Lafite portfolio, Eric Kohler commented, "For Sauternes, the botrytis began very late. It was very difficult for the botrytis to begin. Finally, harvest at Rieussec began on October 10th and ended on October 31st in two to three passes. There was not so much sugar this year and not so much botrytis. It was not as great a year as 2015 or 2017."

Jean-Pierre Meslier of Château Raymond-Lafon commented, "In late October, we had a ten-day period when botrytis took off, and then the rains came. At Raymond-Lafon, we harvested 85% of the crop during October 22-31."

Indeed, the best wines of Sauternes and Barsac in 2018 came in as late as possible—in late October and even into early November. These wines have notably more botrytis character than the earlier harvested wines and, therefore, have livelier acid profiles.

The 2018 wines from Sauternes and Barsac do not possess the profound botrytis signatures of a truly great vintage, nor do they have the marked acidity/freshness of recent years. These are bold, forward wines of great purity and, generally, well-defined tropical and stone fruit expressions, albeit more of a late harvest style in some cases than a textbook Sauternes.

Thanks to Stephen Browett and the team at Farr Vintners for hosting this incredibly well-organized Southwold Tasting and Bill Blatch for arranging all the samples direct from Bordeaux, which is no small task. Salut!

-

Article & Reviews by Lisa Perrotti-Brown MW

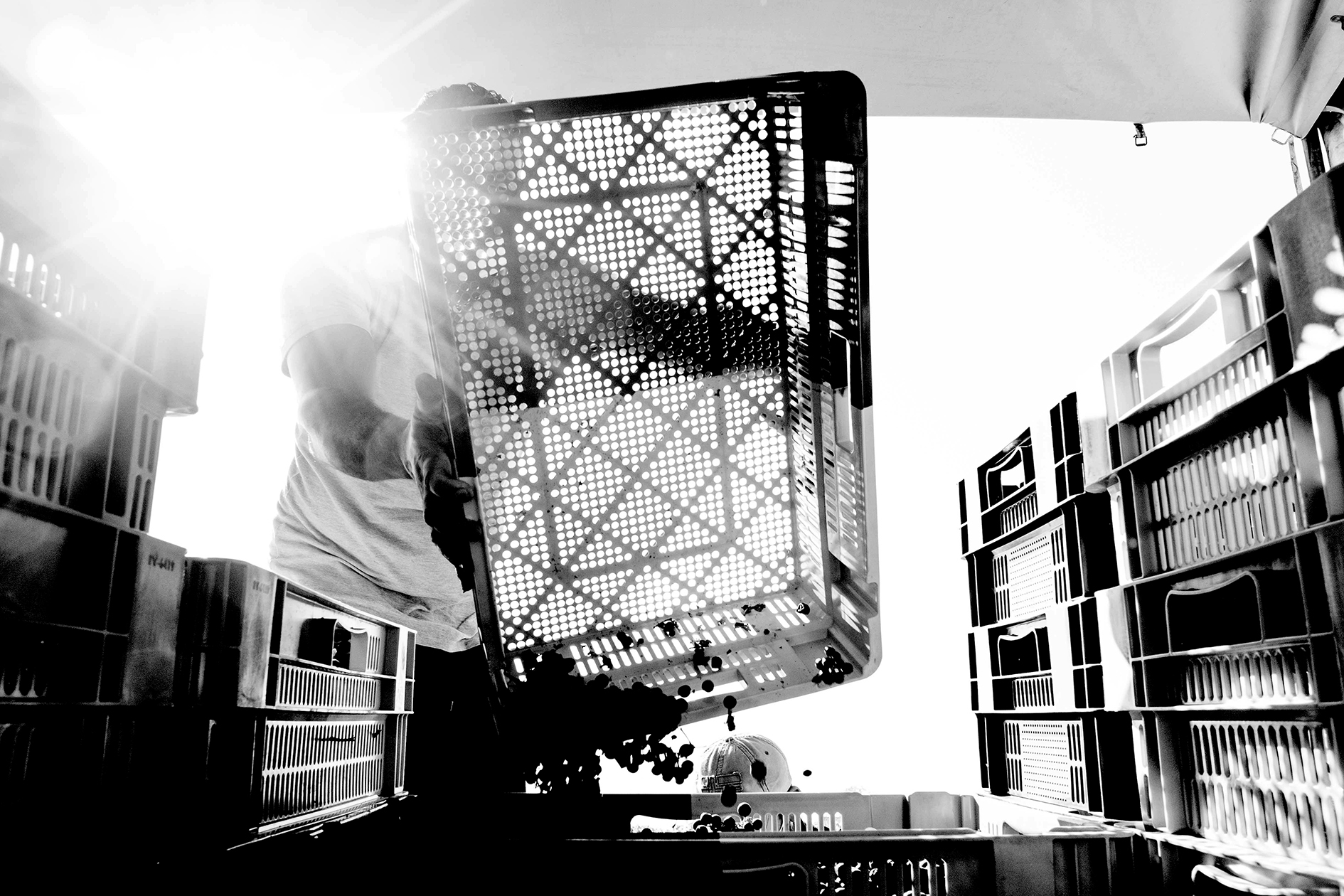

Photos by Johan Berglund

PRODUCERS IN THIS ARTICLE

> Show all wines sorted by scoreMore articles

Cathiard Vineyard New Releases

02nd May 2024

3 tasting notes

Bordeaux 2023 Preliminary Vintage Report and Reviews from Barrel

29th Apr 2024

56 tasting notes

2021 Bordeaux in Bottle and A Modest Proposal

24th Apr 2024

599 tasting notes

Pilcrow’s New Releases

18th Apr 2024

7 tasting notes

Show all articles